My Growth Equation

Posts about Personal Thoughts and Growth

During several months of finding the macro direction of life, I first thought about what my ultimate pursuit was. The conclusion I initially reached through months of contemplation was “compound growth.” While reading writings from various people, I felt that the keyword “compound” was particularly repeated, so I first used that keyword to write about my growth.

Initial Idea

Since October of this year, I’ve been writing a newsletter called Life Interest with a friend. As you can tell from the name, it’s a newsletter about various perspectives and attitudes to have for a compound life. The first article of this newsletter was originally going to describe compound growth with a formula, but the article got too long to include in the newsletter. Since “compound” is in the name, I opened with the basic compound interest formula.

Here, means Future Value. And this value is defined by (Present Value), (interest rate), and (period). I understood this formula as follows:

Interpreted, it means that if you invest a lot of time and have many experiences, you will grow. I’ve been aware of this since around 2010, because in Malcolm Gladwell’s book Outliers, which I read around that time, he argued that if you do something for 10,000 hours, you can become an expert.

Slowing Growth and Its Reasons

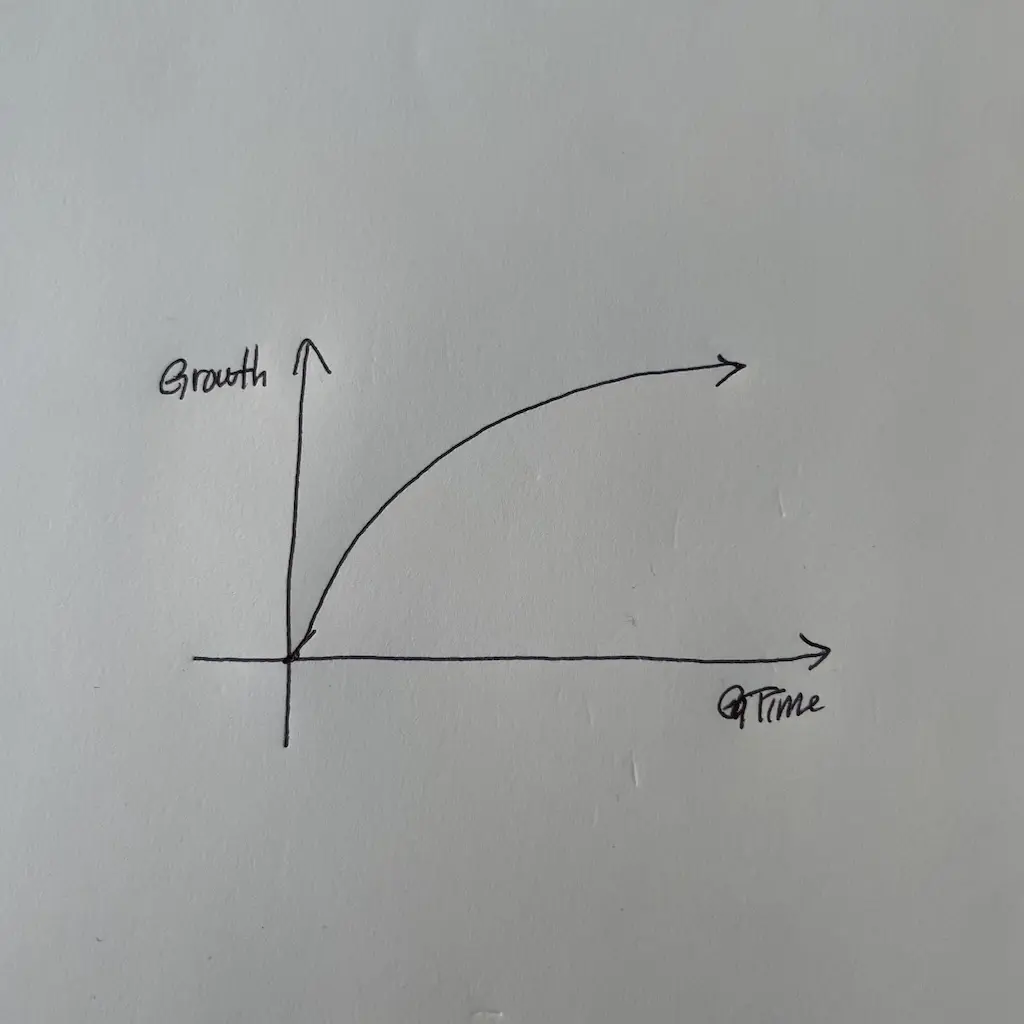

However, after various experiences over a long period, at some point I could feel my growth slowing down like this:

As time passed, I felt growth slowing down as shown below. If the above formula was correct, I should have grown exponentially, but the opposite was happening, so I concluded that the above formula was very wrong. So I changed the formula to:

The factors changed from experience to density, and from time to focused time. It’s gotten a bit more complex, but I can now reflect more specific factors. I see each item as definable as follows:

Density can be expressed as how many meaningful experiences you’ve had relative to time spent. If you have more meaningful experiences, more “aha moments,” in the same time, you can grow faster.

Now let’s look at the item. Why did I specifically add ? I don’t think that simply spending a lot of time on learning something, unless it’s the very beginning, leads to proportionally better results. Especially in the knowledge work field I’m in.

According to Dr. Anders Ericsson who actually researched this, the misunderstanding about the 10,000 hour rule comes from here. Simply spending a lot of time doesn’t improve skills—you can only improve through a process of deliberate practice. I believe that time spent racking your brain to learn and twist something helps with compound calculation. That’s why I added the word focusing.

Making It More Executable

The formula itself is clean without excess, but it’s too abstract to keep in my head and execute, so I kept feeling that execution wasn’t working properly. So I changed this formula from equality to approximation.

And I saw each item as replaceable as follows:

Replacing Focus Time with Execution and Retrospection

Let me give a somewhat extreme analogy. Say you focused with all your nerves to the point of exhausting your stamina, counting how many grains of rice are in one instant rice pack. The focus time is large, but will that help my growth? Not at all.

Focusing on something is good, but only by continuously recognizing why I’m doing this work and checking what choices I need to make to do it better can I not lose direction and use time more meaningfully. In fact, experts, unlike ordinary people, continuously ask questions like “What was I originally trying to do? What will happen if I continue like this?” while working. This is called Reflection In Action.

Now let’s come back to this formula. What this formula means is the great premise that “you must execute, and there must be something to gain from that execution.” However, by extremely shortening the cycle of this execution, it means continuously sensing my situation, grasping new information, and adjusting the situation in real-time to achieve desired goals.

So I’m practicing Reflection in Action every 30 minutes during work. Simply writing down the following 5 questions briefly completes RIA:

- What am I doing right now?

- What was I originally trying to do?

- What will happen if I keep going like this?

- Considering that, what options do I have now?

- Which one should I try first?

Replacing Density with Learning and Time

Sitting down and learning something isn’t the only learning. There’s definitely an efficient way to learn, and the more you apply that method, the more you can learn in the same time. In other words, the density of learning can be determined by the following formula:

But it’s a shame to leave it like this. I’ll attach a note I made recently.

Shifting perspective from time management > energy management makes me feel more at ease and manage time more flexibly. If I can’t focus, from a time management perspective, it’s like “I need to focus quickly” and forcing myself to sit down, while energy management is like “Ah, I’m a bit low on energy right now. Let me take a break and come back.”

Actually, when we think we need to do something more efficiently, we approach it as “let’s manage time well.” But aren’t there many cases where we have a lot of time but don’t want to work, and actually don’t? At those times, motivation has dropped or we’re physically tired. That is, we need energy to actually do something. So, it can be changed like this:

Moreover, the higher the proportion of total learned memories that remain as long-term or implicit memory, the more efficient the learning. So let’s include that ratio in the formula.

But doing this might lead to optimization by extremely reducing energy. This would lower learning quality and result in overall loss. In the end, Learning and Energy are actually proportional. With slight adjustments possible. Therefore, we need to multiply by the total amount of energy.

Conclusion

Combining the formulas above gives:

In other words, we can conclude that continuously executing and retrospecting, increasing the efficiency of learning itself (learning more with less energy), and increasing the total amount of energy helps. I plan to continuously revise this over months and years, but as of November 2024, this is how it stands.