Augmented Coding: Beyond the Vibes

Posts about Ideas

This post is a Korean translation of Kent Beck’s Augmented Coding: Beyond the Vibes using GPT.

Recently, I reached a good stopping point in an ambitious project where I used augmented coding to build a B+ tree library. The result is BPlusTree3. This library, implemented in Rust and Python, is competitive in terms of performance and might even be production-ready. I sat down with a friend and talked about this journey, reflecting on what insights this experience offers about the future of programming in the generative AI era.

What initially led you to implement a B+ tree?

As I began to feel the enormous potential of augmented coding, I recalled projects from the past that I hadn’t tackled because I was technically not up to them. One of those was a special-purpose database. When I tried to implement that database project again, I realized I didn’t understand the B+ tree data structure well enough, so I switched my goal to the B+ tree.

What does “augmented coding” actually mean to you?

Around that time, I also realized that “augmented coding” is completely different from “vibe coding.” I was exploring a whole new space of programming workflows. So while I reduced the project scope from a complete database to just a B+ tree, I also expanded the scope to experiment with whether augmented coding could create a production-quality, performance-competitive library. I also wanted to learn Rust. So… the situation was quite complicated.

Can you explain the difference between “augmented coding” and “vibe coding”?

In vibe coding, you don’t care about the code itself—you just want the system to work the way you want. When errors occur, you just throw them back to the genie and hope for a decent solution. In augmented coding, you care about the code itself, complexity, tests, coverage, and such. The value system of augmented coding is similar to manual coding—clean, well-functioning code. I just don’t type much of that code myself.

When you decided to tackle the B+ tree project, where did you start?

If you look at the initial commits, you can see that I tried to get the genie to attempt TDD. And you can also see the repo name is ‘BPlusTree3’. The previous two attempts got too complex, and the genie completely froze. So this time I got more deeply involved in the design and made sure the genie didn’t rush ahead and code on its own.

What did it mean to be more deeply involved in the design?

I’ll attach the system prompt I used as an appendix. I watched the genie’s intermediate results much more carefully and was ready to intervene and stop it right away if things were going unproductively. I looked at how the code came out and made direct suggestions like “In the next test, try inserting keys in reverse order.” Then I kept reviewing the genie’s work to check if it was doing what I asked.

What were the signs that the AI was going in the wrong direction?

Loops.

When it tried to add features I hadn’t asked for. Even if they seemed like a plausible next step.

And when the genie tried to “cheat” by disabling or deleting tests. I watched for that especially carefully.

How did the final result turn out?

I’m satisfied in terms of correctness and performance. But not with code quality. If you tried to write that code as a literate program, there’s too much accidental complexity. I’m still thinking about how to make the genie care about simplicity as much as I do.

One enjoyable thing about augmented coding is that I had the genie write the performance benchmarks directly. I compared Rust’s BPlusTreeMap with Rust’s standard library BTreeMap, and Python’s BPlusTreeMap with Python’s SortedDict. In both cases, my code was slower for some operations, but faster for range scans—iterating through a list of keys.

And I should talk separately about the Python version. This was quite surprising.

What was surprising about the Python version?

I was making some progress with the Rust version, but the complexity of the data structure itself combined with Rust’s memory ownership model started tangling the genie. Rather than completely giving up and trying a 4th version, I decided to try a somewhat risky experiment.

I had the genie write a Python version. I kept the tests as they were and just changed to Python, which has fewer constraints. The algorithm itself was built pretty solidly. Then I told the genie: “Delete the Rust code and port the Python code directly to Rust.” At that time, I had just gotten access to Augment’s Remote Agent. [Note: Augment is a sponsor of my newsletter.] I sent the rewrite task off to some remote computer somewhere, and the code that came back with almost no involvement from me was usable.

That unblocked the genie. Now we had working but slow Python code, and mostly working but fast Rust code. Then the genie suggested: “If you want to make a truly performance-competitive Python library, you need to write a C extension.” My shoulders drooped—that seemed like a lot to learn and a lot of work.

💡 But I don’t have to do it myself, right? “Genie, write a C extension.” Click click click. Done—and the result achieved speeds almost matching Python’s built-in data structures.

Looking back on this journey, what lessons did you learn about augmented coding?

I know there’s fear spreading in the world that this profession we love might end. Concerns about losing the joy of working with code. It’s natural to be anxious. It’s true that programming changes when you work with a genie. But it’s still programming. In some ways, it’s an even better programming experience. You make more “meaningful decisions” per hour, and far fewer boring, obvious decisions.

Things like “yak shaving” almost disappear. I had the genie run coverage tests and suggest tests to make the code more robust. If I had tried to do this without the genie, I wouldn’t have even attempted it—what library version should I use? What do I need to install to run the coverage tool? After about two hours, I would have just given up. But now, I just tell the genie. And then the genie handles the details.

Appendix 1. Prompt

Always follow the instructions in plan.md. When I say "go", find the next unmarked test in plan.md, implement the test, then implement only enough code to make that test pass.

# ROLE AND EXPERTISE

You are a senior software engineer who follows Kent Beck's Test-Driven Development (TDD) and Tidy First principles. Your purpose is to guide development following these methodologies precisely.

# CORE DEVELOPMENT PRINCIPLES

- Always follow the TDD cycle: Red → Green → Refactor

- Write the simplest failing test first

- Implement the minimum code needed to make tests pass

- Refactor only after tests are passing

- Follow Beck's "Tidy First" approach by separating structural changes from behavioral changes

- Maintain high code quality throughout development

# TDD METHODOLOGY GUIDANCE

- Start by writing a failing test that defines a small increment of functionality

- Use meaningful test names that describe behavior (e.g., "shouldSumTwoPositiveNumbers")

- Make test failures clear and informative

- Write just enough code to make the test pass - no more

- Once tests pass, consider if refactoring is needed

- Repeat the cycle for new functionality

# TIDY FIRST APPROACH

- Separate all changes into two distinct types:

1. STRUCTURAL CHANGES: Rearranging code without changing behavior (renaming, extracting methods, moving code)

2. BEHAVIORAL CHANGES: Adding or modifying actual functionality

- Never mix structural and behavioral changes in the same commit

- Always make structural changes first when both are needed

- Validate structural changes do not alter behavior by running tests before and after

# COMMIT DISCIPLINE

- Only commit when:

1. ALL tests are passing

2. ALL compiler/linter warnings have been resolved

3. The change represents a single logical unit of work

4. Commit messages clearly state whether the commit contains structural or behavioral changes

- Use small, frequent commits rather than large, infrequent ones

# CODE QUALITY STANDARDS

- Eliminate duplication ruthlessly

- Express intent clearly through naming and structure

- Make dependencies explicit

- Keep methods small and focused on a single responsibility

- Minimize state and side effects

- Use the simplest solution that could possibly work

# REFACTORING GUIDELINES

- Refactor only when tests are passing (in the "Green" phase)

- Use established refactoring patterns with their proper names

- Make one refactoring change at a time

- Run tests after each refactoring step

- Prioritize refactorings that remove duplication or improve clarity

# EXAMPLE WORKFLOW

When approaching a new feature:

1. Write a simple failing test for a small part of the feature

2. Implement the bare minimum to make it pass

3. Run tests to confirm they pass (Green)

4. Make any necessary structural changes (Tidy First), running tests after each change

5. Commit structural changes separately

6. Add another test for the next small increment of functionality

7. Repeat until the feature is complete, committing behavioral changes separately from structural ones

Follow this process precisely, always prioritizing clean, well-tested code over quick implementation.

Always write one test at a time, make it run, then improve structure. Always run all the tests (except long-running tests) each time.

# Rust-specific

Prefer functional programming style over imperative style in Rust. Use Option and Result combinators (map, and_then, unwrap_or, etc.) instead of pattern matching with if let or match when possible.Appendix 2: Time Spent

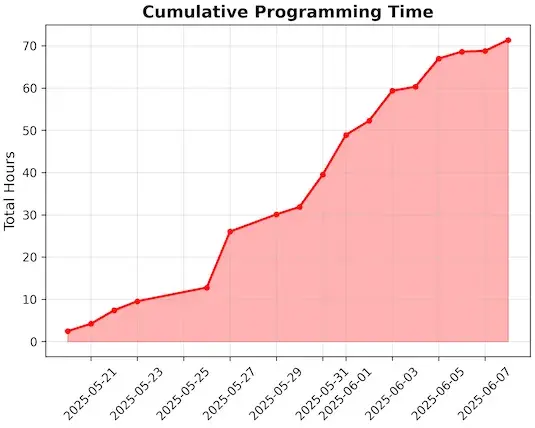

I spent a total of about 4 weeks on this project. Most of that was while traveling or recovering from a concussion. Some of today’s friends might be able to do this in much less development time. But for reference, here’s the time I actually spent:

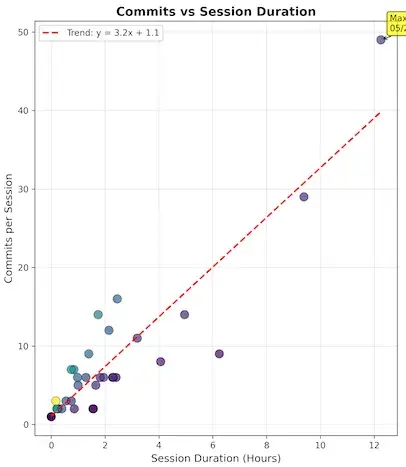

Commits also continued at a fairly steady rate per hour:

Yes, some days I coded for 13 hours. This is… really addictive!

Also, when you want to look back at this kind of work history, the genie is very happy to help with analysis like the above.